Lionel Shriver knew she was going to annoy people. “Inviting a renowned iconoclast to speak about ‘community and belonging’ is like expecting a great white shark to balance a beach ball on its nose,” she said. She then used her keynote speech at the Brisbane writers’ festival to tear into the argument that writers – most particularly white writers – are guilty of “cultural appropriation” by writing from the point of view of characters from other cultural backgrounds.

Referring to incidents in which two members of student government at an American university faced impeachment after attended a “tequila party” wearing sombreros, and reports of a ban on a Mexican restaurant from giving out sombreros, the author of We Need to Talk About Kevin said: “The moral of the sombrero scandals is clear: you’re not supposed to try on other people’s hats. Yet that’s what we’re paid to do, isn’t it? Step into other people’s shoes, and try on their hats.”

The response was instant. Sudanese-born Australian social activist Yassmin Abdel-Magied, who was attending the event, walked out and then quickly penned a comment piece which argued that Shriver’s speech was “a celebration of the unfettered exploitation of the experiences of others, under the guise of fiction”.

The argument is one of the most pointed yet in a debate that has a long history across literature, music, art and performance. While fiction might be the catalyst for this discussion, in the eyes of Abdel-Magied and others the issues are deeply rooted in real-world politics and a long history.

The image of the blackface minstrel artist of 1830s America – the white performer painted up to look like a caricature of an African-American person and performing comic skits – is perhaps the most oft-invoked example of cultural appropriation from history. The racial dynamic of minstrelsy was complex – it was performed by African-American and Anglo actors alike – but while African-American performers often sought to gain financial security from the practice and in some cases use their platform to counter negative public stereotypes of themselves, white performers reinforced those stereotypes. This occurred within a society which still had not abolished slavery, and in which the political power dynamic was very much racialized. As the civil rights movement grew, so did criticism of white people attempting to exploit the images and experiences of people of colour for social and financial gain.

This pattern is repeated around the world, particularly in places that experienced colonisation and slavery, such as India, Australia and South Africa. As scholars, artists, activists and writers of colour fought to gain access to predominantly white institutions and public spaces, and gained visibility in the cultural sphere, they began to criticise the inaccurate representations of themselves they saw created by and for the profit of others.

The issue has been heavily explored within the academies but has gathered momentum in popular culture over the past decade. It underpins criticism of, among other things, Iggy Azalea’s “sonic blackness”, Coldplay’s “myopic construction of India” in their music videos, and Miley Cyrus’s dance moves. Director Cameron Crowe recently apologised for casting Anglo-American actor Emma Stone as a “part-Asian” character in the 2015 film Aloha – not the first time a white actor has been cast to play a character from a different racial background in mainstream cinema. The argument has been assisted particularly by the feminist community’s focus on “intersectionality” – crudely the idea that discrimination takes on different forms depending on the race, class and/or gender of the person discriminated against.

The charge of “cultural appropriation” is not confined to fiction, but at the moment that’s perhaps the most hotly contested terrain. In March, Harry Potter author JK Rowling was accused of appropriating the “living tradition of a marginalised people” after a story published to her Pottermore website drew upon Navajo narratives about skinwalkers. Shriver herself mentioned the case of white British author Chris Cleave, whose novel The Other Hand is partly narrated by the character of a teenage Nigerian girl. “In principle, I admire his courage,” Shriver said. She then went on to detail reviewer Margot Kaminski’s concerns that Cleave was “exploiting” the character, that he ought to be “taking special care” with representing an experience that was not his own.

Shriver took aim at the suggestion that an author should not “use” a character they created for the service of a plot they imagined. “Of course he’s using them for his plot!” she said. “How could he not? They are his characters, to be manipulated at his whim, to fulfil whatever purpose he cares to put them to.

“What boundaries around our own lives are we mandated to remain within?” asked Shriver. “I would argue that any story you can make yours is yours to tell, and trying to push the boundaries of the author’s personal experience is part of a fiction writer’s job.”

While it seems obvious that writers of fiction will endeavour to write from perspectives that are not their own, many writers of colour argue there is a direct relationship between the difficulties they face trying to make headway in the literary industry and the success of white writers who depict people of colour in their fiction and who go on to build a successful literary career off that. The difference between cultural representation and cultural appropriation, by this logic, lies in the white writer telling stories (and therefore taking publishing opportunities) that would be better suited to a writer of colour.

Some writers argue that it works in reverse, too. In an event for the Guardian in November last year, Booker Prize-winning author Marlon James said publishers too often “pander to the white woman” (the majority of the book-buying public), causing writers of colour to do the same. In a Facebook post responding to novelist Claire Vaye Watkins’ widely circulated essay On Pandering, James said that the kind of story favoured by publishers and awards committees – “bored suburban white woman in the middle of ennui experiences keenly observed epiphany” – pushed writers of colour into literary conformity for fear of losing out on a book deal.

Speaking to Guardian Australia, Indigenous Australian author and Miles Franklin winner Kim Scott says it’s crucial to listen to the voices of marginalised people who may not be given enough space to tell their own stories. “Stories are offerings; they’re about opening up interior worlds in the interests of expanding the shared world and the shared sense of community. So if there’s many voices saying we need more of ‘us’ speaking ‘our’ stories, from wherever they’re saying that, then that needs to be listened to.”

Omar Musa, the Malaysian-Australian poet, rapper and novelist, told Guardian Australia: “There is a history of stereotypes being perpetuated by white writers and very, very reductive narratives. People are just generally a lot more wary of that.”

Musa says white writers should read, support and promote the work of writers of colour before attempting to encroach on that space themselves, if that is something they want to do. But he admits he finds the issue difficult; the suggestion that writers shouldn’t move outside the boundaries of their own experiences comes into direct conflict with what he sees as the purpose of fiction: to empathise with and understand other people’s lives.

If you’re going to write from someone else’s perspective, Musa says, it’s important to avoid stereotypes, especially “if you want to make the characters rich and flawed as a good character should be”.

![Australian author Maxine Beneba Clarke. ‘There are two schools of thought about [cultural appropriation] … I don’t know what the answer is but I can understand both perspectives.’](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/f18fe39b0ecb8571512e1f677e73cf8980833a2a/0_0_4928_3264/master/4928.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none)

Musa has his own experience of writing across the cultural divide. His first novel, Here Come The Dogs, was told from the perspective of a character with a Samoan background. Musa says accepting criticism is a crucial part of this process: “There will be people who will tell you that maybe you didn’t quite get this right, and you just have to cop that flack.”

Maxine Beneba Clarke is an Australian-based writer of African-Caribbean descent. Her memoir The Hate Race was prompted by a torrent of racial abuse; her collection of short stories, Foreign Soil, was published to great acclaim after she won the Victorian Premier’s Literary award for an unpublished manuscript in 2013. “I think there are two circumstances in which I’ve written outside of the African diaspora,” she says. “In both cases they were pieces of short fiction and the process of writing them took several years, just because of that consultation.”

Beneba Clarke believes consultation is crucial, but so is examining your own impulse to write from the perspective of another. “What does it mean to be a writer who is not a minority writer and wanting to diversify your literature? How do you do that? I think that was the opportunity for conversation that was missed [in Shriver’s speech] ... How do we feel about writing each other’s stories and how do we go about it? What’s the respectful way to go about it?

“In some ways it comes down to personal ethics,” she says. “Whether you feel you are doing no harm; whether you feel you are doing it sensitively; and, I suppose, whether the publisher or the reader agrees that you have done it sensitively.”

Helen Young from the University of Sydney English department says fiction can have a very real impact on marginalised people. “Individual books have an impact on individual lives, but representation overall creates a space and an environment in which people can feel like it’s OK to be who they are.”

The politics of representation is a huge issue in the science fiction and fantasy worlds too, says Young. This was exemplified by the recent campaigns against a perceived leftwing bias in the Hugo awards, in which disgruntled rightwing science fiction and fantasy writers argued the awards were being diminished by what they saw as the tendency of voters to prefer works “merely about racial prejudice and exploitation” and the like over traditional swashbuckling adventures.

Referring to the JK Rowling incident, Young says just because fantasy is often thought of as escapist, doesn’t mean those stories don’t matter, or that authors should not treat the source of their inspiration with respect. “They’re still the lived, sacred stories of living cultures,” she says. “They’re the beliefs of real people. So if from a western perspective you go, ‘oh well, it’s just mythology, I can do whatever I like with it’, that’s a problem.”

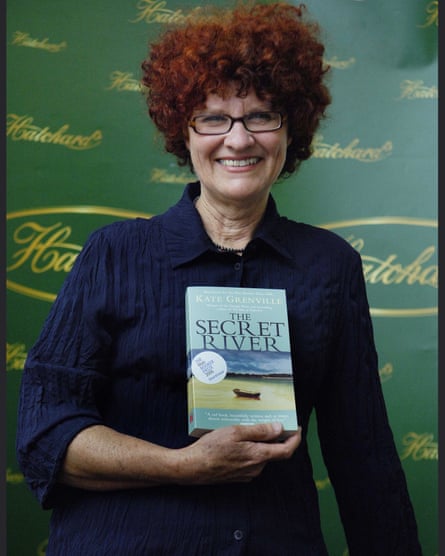

In some respects, the ground seems to be shifting. When Kate Grenville wrote her highly acclaimed historical novel about colonial Australia, The Secret River, in 2005, she avoided writing from the perspective of Indigenous characters because she felt it was “beyond” her. Speaking to Ramona Koval on ABC radio, she said: “What I didn’t want to do was step into the heads of any of the Aboriginal characters. I think that kind of appropriation ... there’s been too much of that in our writing.” In her novel The Lieutenant, the sequel to The Secret River, however, Grenville did venture into depicting more rounded Indigenous characters, but only after deep and careful engagement with the historical records upon which her characters were based.

All the writers who spoke to Guardian Australia say they believe that discussing the issue of cultural appropriation is crucial, but the tenor of that discussion matters. They say that making a mockery of marginalised people’s concerns about representation and appropriation does not constitute a constructive discussion.

Scott, who has previously suggested a moratorium on white authors writing about Indigenous Australia, says white writers could use fiction itself to explore the tension about representation. “Even the desire to inhabit the consciousness of the other, that can be explored in story.”

For Musa, the shift needs to go beyond books: “You probably can’t have a change in literary culture without a change in the whole culture of the country,” he says.

On the question of progress, in Australia at least, Beneba Clarke says: “There are two schools of thought about this: that Australian literature is not diverse enough for Anglo-Australian writers to be even considering writing from other cultures, and the other school of thought is, well, how do we diversify literature then, given that most of our writers are Anglo-Australian? Are we locking ourselves into an inevitably whitewashed world of literature?

“And I don’t really subscribe to either view; I don’t know what the answer is but I can understand both perspectives. But I think what I absolutely can’t understand is disregard for any kind of consultation and an inability to understand when people of colour are outraged.”